1999-2002: My childhood in Russia (in Novomirskiy and in Azov, Moskovskaya Street)

I'm the one in the T-shirt.

I'm the one in the T-shirt.Year 1999. My parents simply didn't dare to emigrate to New Zealand. Other people, another language, and then also so far away from their own parents. Instead, they left our house to the grandparents for sale and moved to the south of Russia – to a small village called Novomirskiy, just thirty kilometers from Grandpa Yura and Grandma Lina.

Our apartment consisted of a single, thirty-square-meter room, which served as a kitchen, living room, and bedroom at the same time. To separate the kitchen from the living and bedroom, we used the boxes of our new furniture that we bought after the move.

The apartment was without a water connection, so my parents had to fetch water from a well. The toilet consisted of an outhouse in the yard. Since there was no built-in heating, on cold days we used a small electric heater that we placed in the middle of the living room.

I started school while my parents worked as English teachers at a school around the corner. My mom also taught German in lower classes. After school, I spent most of my time on the school playground with my new friends and also attended a karate course there.

Although Novomirskiy was not a dream place, it felt more like home to me than Uzbekistan. Here, everyone spoke Russian, which gave me a sense of connection. Despite the lower standard of living compared to Uzbekistan, I felt happier in Novomirskiy! It was probably my friends who influenced my happiness, not whether I used a heated toilet or an outhouse to do my business.

During the holidays, Grandpa Yura came with his sparkling clean Volga and took us all to Kharkovskiy, to the newly built house of my grandparents. The journey took us through Kugei and Poltava, where Grandpa sold some large sacks of sunflower seeds or other seeds for a few hundred rubles on the way. After the short stops in the villages, we continued to Grandma Lina, who was already waiting for us with a richly set table.

My grandparents lived together with my great-grandmother, Anna Solomonova, Yura's stepmother. She could hardly move because she had a large wound along her calf. Therefore, she spent most of the time sitting or lying quietly on her bed. Sometimes Grandpa scolded her when she scratched the wound, which was already difficult to heal. One morning, she didn't wake up anymore. She was buried in the nearby cemetery. Uncle Sasha also attended the funeral, as he lived just two houses away with his wife, Aunt Olja, and their daughter, Ksyusha.

My cousin was not Uncle Sasha's biological daughter. She was a year older than me, and whenever I visited the grandparents, we played together. At Aunt Olja's house, there was a VCR with tapes like "The Lion King," "Mulan," or "Pocahontas." Some of the tapes were from Uncle Sasha. He owned many horror movies, mostly of a bloody nature, like "Freddy Krueger," "Jason," "Scream," and various zombie and werewolf movies. Ksyusha and I watched them all.

During the three-month summer vacation, I went almost daily with Ksyusha, Uncle Sasha, and Grandpa Yura by carriage to a nearby pond surrounded by reeds, where we swam or fished with Grandpa and then cooked Ucha, a Russian fish soup, right by the pond.

How My Fear of Deep Waters Began

I couldn't swim, so I always relied on wearing a floatation ring whenever I was in the water. The ring was so large that I would fall straight through the hole if I raised my hands. Normally, I supported myself on the ring with my armpits to ensure I didn't slip through the hole. But on this day...

I was in the water with Ksyusha and Dima. Ksyusha called out to our Opa Yura, who was standing on the shore eating a boiled potato: "Opa Yura, throw us the ball!"

The ball landed not far from Ksyusha in the water. She retrieved it and threw it into the air before hitting it towards Dima. Dima caught the ball and played it back to me in the same way. The ball flew high into the air, and I reached out my arms to catch it. Unconsciously, I leaned on the floatation ring to jump higher. Just as my fingertips barely touched the ball, I was pulled down by gravity. I began to sink deeper and couldn't get any air. Water entered my nose and mouth as I continued to sink. The sun seemed dimmer, and the light faded as I descended. Panic filled my body, and I thought this might be the end of my life. Suddenly, I felt someone grab me from behind and push me to the surface. When I finally emerged, I gasped for air and coughed painfully. It was my uncle who had saved me. He held me close as we returned to the shore. This traumatic experience triggered a profound fear of deep water in me, which persisted into adulthood.

To the Sea of Azov

After a successful wheat harvest in the autumn, Opa Yura sold his beloved Volga and bought a red Lada instead. But even this spacious car was too small to take us to the highlight of the summer holidays – the Sea of Azov, a hundred kilometers away. Opa sat behind the wheel, Dima in the passenger seat, Uncle Sasha with Aunt Olja and Ksyusha in the back seat. And I was in the trunk, where I watched the cars behind us through a window. Although it wasn't allowed to transport people in the trunk, the only time we were actually stopped by the police, we managed to bribe our way out with a hundred-ruble note (for a nice evening with shashlik).

At the end of the summer holidays with my grandparents, my parents, Dasha, and I moved again, this time to Azov. My youth in Azov will enrich me with the most adventurous memories.

Moskovskaya Street, Azov

The 2000s. It was barely a year since we moved to Novomirskiy that we packed our things again and moved to the small town of Azov on Moskovskaya Street, about fifty kilometers away.

Living in a high-rise was a completely new experience for me – eight whole floors high, something I had never experienced in Uzbekistan or Novomirskiy! There was even an elevator, although it smelled terrible of urine. At first, I often imagined the elevator was some kind of spaceship that took me high enough to overlook the entire city. I wanted to go even higher, but the staircase leading to the roof was usually blocked by a locked gate. Only occasionally was I lucky enough to find it unlocked, allowing me to reach the roof of the high-rise. From there, I could even see the other side of the city, where my new school was located.

The roof always had a windy atmosphere. The first time I bravely stepped to the edge of the high-rise and looked down at the tiny people below, I was struck by the thought of how a strong gust of wind could push me down and I would fall to the ground. I imagined lying on the ground, dead, until my mother found me and burst into tears. This thought instilled in me an overwhelming fear of heights. Quickly, I returned to the center of the high-rise and never dared to approach the edge again.

By now, I was in second grade and had quickly settled into the new school. I quickly made friends, including Timur, Ivan, Wasja, and several others from my class. During school breaks, we spent a lot of time together, roaming around Azov and searching for exciting adventures.

Girls didn't interest me at that time. I found them boring and annoying. The only exception was my class teacher. I sat in the front row and could smell her sweet perfume. Her penetrating, blue-eyed gaze seemed to wander into infinity and constantly distracted me from the exercises we were supposed to do during silent work. To catch her attention, I secretly kept drawing on my school cabinet, then sadly told her that someone had scribbled on it. She comforted me with a hug. But after I was almost caught by the principal once, I stopped.

Other than that, I was a model student. In both second and third grade, I received all A's, the highest possible grades, on my report card, for which I received small awards from the school at the end of the school year.

After school, I always played with my new friends on the schoolyard before heading home. Instead of taking the normal route, I preferred a shortcut I discovered over a fence and a wall. From there, I could get to the back of our high-rise – to the courtyard where the neighbor kids sometimes played. There stood a large swing where, with enough momentum, you could even achieve three hundred and sixty-degree rotations.

A little further at the end of the high-rise, behind a road, was an abandoned construction site overgrown with weeds. Sometimes, I climbed around on the scaffolding with my school friends or tried to catch one of the small lizards. I only succeeded if I didn't try to grab them by the tail, as they would simply shed it and disappear quickly into a slit between the stones. If I did manage to catch one, I took it home and put it in a jar lined with grass.

Our one-room apartment was on the first floor. The room was amusingly not square but triangular on one side. At the tip of the triangle was a window with a fold-out table. I did my homework there. On the other side of the living room was my bed, and right in the middle of the living room was a double bed where my parents and Dasha slept. Above, on the wall, hung a huge oriental carpet that we brought from Uzbekistan. Opposite the double bed was a massive wall unit with clothes, books, a television, and a VCR. Finally, we had running water in the apartment; and thus, also a toilet and a built-in heating system.

Without a car and with no connection of the city to Novomirskiy, my parents had to find new work. My mom was hired as a teacher, but Dima was initially without a job. However, that changed quickly when Mama found an interesting position advertised in the newspaper at a regional radio station. The station was looking for a presenter, and my father was immediately hired because he had a deep voice, was eloquent, and pronounced each word very clearly. He was generally a very extroverted person and could quickly make friends with various people with his manner and humor.

The Radio Presenter

One evening, Dima took me to his work because we wanted to surprise Mama a little. Outside the entrance to the building, we were spotted by a surveillance camera. After a friendly wave to the camera, the sturdy, metal entrance door opened by itself. It was a security guard who let us into the building late at night.

When I entered the recording studio with Dima, I was thrilled. So many buttons to press. A blink here, a glow there! With my mouth open and without taking my eyes off the cockpit, I slowly sat down in the chair. Within a short time, my open mouth turned into a mischievous grin: I felt like the captain of a spaceship. With the so-called keyboard, I could have my name displayed on one of the screens (even though it took a thousand years to type).

Then Dima dictated a few words to me with birthday wishes for Mama. He then spoke these words into a microphone. On her birthday, Mama was surprised in the morning with our birthday greeting on the radio during breakfast. She was very happy about it.

Karaoke with Grandparents

At the end of autumn, Galja and Gogi came to visit from Uzbekistan for two weeks. I remember Dasha, Galja, and I singing karaoke and dancing while our VCR played a song from the Bremen Town Musicians. Gogi mostly sat next to us, trying out different types of beer, with a broad grin on his face. In fact, he managed to try all the types of beer available in Azov in those two weeks.

The Christmas Event

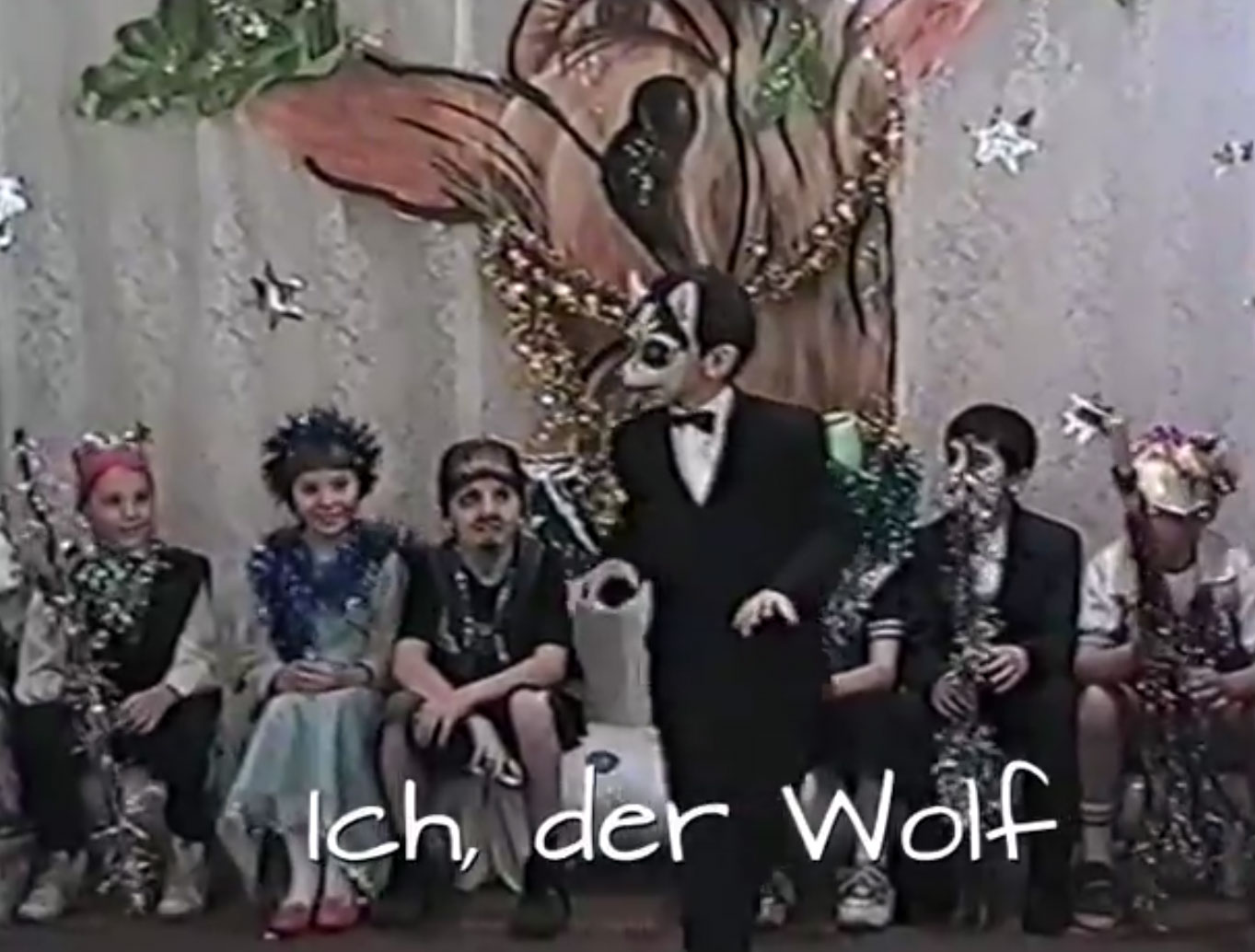

In December, a special event took place at my school. In a small play, the students had to rescue Djed Moros (Father Frost) to receive Christmas presents. Several weeks before the event, the roles were assigned, and we memorized our lines. At home, my mother sewed a matching plush tail for me, which belonged to my role as the villain, a wolf. In the play, I tried to eat a friend of Pinocchio who was wandering alone. But she was saved in time by Pinocchio and his friends, who pulled a sack over my head.

I act a wolf at school.

I act a wolf at school.

A few days later, on December thirty-first, we were given presents at home. Djed Moros, who rang our doorbell and brought his Snegurochka, quickly turned out to be Dima. The Snegurochka, whom I saw for the first time, was a colleague of Dima's, whom Mama was sometimes jealous of. Because of her, there were occasional arguments between my parents. But on this holiday, Mama pretended that Snegurochka was a wonderful person.

After I recited a winter poem called "Snowflake Dance" by Tatjana Volgina, Djed Moros took out a magic cube, an illustrated book about UFOs, and a kind of metallic Lego from a red bag and handed it to me. Dasha received a doll and a pink stroller to play with.

My Walkman

Galja and Gogi came to visit from Uzbekistan again. Occasionally, I accompanied Gogi to church or to the Don River, where older boys jumped into the water from the bridge. I always boasted that I could do that too and claimed that I had just forgotten my swimming trunks. In reality, I would never have dared to do it because of my fear of deep water, even though I could swim by now.

One day, when I was with Gogi at the Azov Bazaar, he bought me an olive-green Walkman with cassette tapes. Proudly, I attached it to my belt for my adventures in Azov. Gogi promised to buy me even cooler stuff; I just had to wait until he moved to Azov with Galja. And indeed, they did that soon, saving me from the increasingly intense conflicts between my parents...

Future Learning from My Childhood in Novomirskiy: How happy I feel has nothing to do with whether I have a heated toilet or an outhouse at home. What makes me happy are social relationships and experiences.